Glenn Freemantle won an Oscar in Sound Design for his work on Gravity. I had the pleasure of hearing him talk about his work at Glasgow Film Festival 2015, including what it's like to design sound for a film set in the vacuum of space.

Part of the fun in attending a film festival is joining the discussion that arises before, after and in between screenings. Festival-goers have a real appreciation for the entire process of filmmaking. What an even greater pleasure it is to have the makers of festival films join the conversation. Working as Festival Marketing Assistant for Glasgow Film over the past few months, I’ve had the pleasure of attending the series of 'Behind the Scenes' talks at the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow (CCA). The festival is in part to blame (that’s not true – I’m entirely to blame) for my recent silence. Though anyone who’s worked a festival will understand how immersed you become in the programme, the promotion and then making the most of every minute while it’s running.

During this time, I saw many opportunities for topics I could expand into blogs. The 'Behind the Scenes' discussions with filmmakers prompted many of those moments. These discussions often highlighted interplay between the creative and technical, the constraints of physics or finance against the vision of the filmmaker.

Glenn Freemantle’s Sound Masterclass at Glasgow Film Festival 2015 (GFF15) was one such example. I count science-fiction film Gravity as one of my favourite films, and I recognise that this largely down to the use of sound. (I'll forgive the scientific inaccuracies in Gravity because these compromises place a greater focus on the story.) Sound Designer Glenn Freemantle won an Oscar for his work on Gravity and the discussion was high on my list of must-sees. Presented with designing the sound for a film set in the vacuum of space, how would one tackle this problem? Glenn’s answer is beautifully simple: have the audience experience the sound of the film through the vibrations in the astronaut’s space suits.

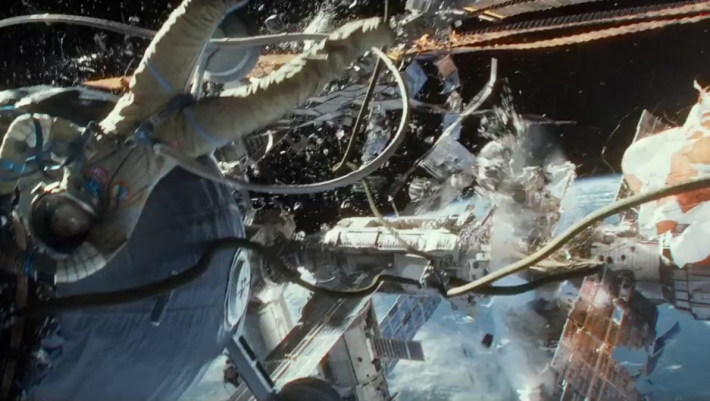

With no air particles to vibrate and carry sound, it wouldn’t be possible to hear anything beyond their space suits. The rapidly approaching tide of debris in orbit would be as silent as it is deadly. In the film, the approach of the debris is marked by dramatic orchestral punches, representing the increased tension rather than trying to accurately replicate the sound of the approaching debris. Even with the degree of destruction that's wreaked throughout the film, we only experience audibly that which has a direct impact on our protagonist's space suit.

Credit: Warner Bros

Arguably, sound does exist in space, though it’s not within the range of human hearing. NASA has shown, with recordings made over recent years, that sound in space exists as electromagnetic vibrations. Charged electromagnetic particles from Solar Wind, ionosphere and planetary magnetosphere vibrate in interstellar space. These vibrations can be recorded within the range of human hearing with the use of Plasma Wave antenna. The NASA Voyager, INJUN 1, ISEE 1 and HAWKEYE space probes have all used this specialised equipment to capture the sounds of this ionized gas vibrating. You can hear some of the recordings made by Voyager 1 here. When converted into a range of sound that we can hear, the result is quite eerie; NASA recommend the clips as appropriate Hallowe’en listening.

It seems the only realistic way to portray the astronauts’ experience of space is through the vibrations of their suits. Every little movement and impact is noticeable when there’s little else to hear. No wonder Dr. Ryan Stone is nauseous at the start of the film.

This technique is not just realistic. It also helps us to identify closely with the central character, because we can hear everything that she does, and very little else. As the vibrations she hears are so closely linked to her movements, we truly feel like we inhabit her skin, or at least, her spacesuit. This connection with the character continues even when the camera zooms out to take in some beautiful shots of surrounding space, though the result is a disorientating experience.

These choices make further sense in the context of a point that Glenn stressed throughout his talk: how the sound needs to be a vehicle for story and emotion. He noted how in different emotional states things can sound quite differently. The sound designer needs to be perceptive of these states to create the desired effect. (At this point, I was reminded of the use of sound in another GFF15 film When Animals Dream, in which the use of sound and music helps the viewer to connect closely with the central character. Such identification is a strange experience as the central character turns out to be a werewolf, typically ‘The Other’ in the horror genre; this subversion of expectation is very satisfying.)

Glenn noted how, rather than trying to realistically represent every action on screen with an appropriate sound, it's more effective to select sounds to highlight and using them as a way of tapping into the characters’ emotional states. He discussed the whining sound of radio contact in Gravity, which is used to emotionally manipulate the viewer, giving an audible reminder of hope and connection to Earth, like a lifeline. The removal of the sound of radio contact in the film is a sign of diminishing hope.

For a film set in a soundless vacuum, Gravity is a treat for the ears. This is undoubtedly the result of how Glenn taps into the characters’ emotional states. By hearing the sound of the film through Dr Ryan Stone’s spacesuit, we both form a close connection with that particular character and experience an accurate representation of what it’d sound like to be an astronaut in space. Gravity is guilty of some gaping scientific inaccuracies, though they are the interests of good storytelling. I’m willing to suspend disbelief that the Hubble Space Telescope and the International Space Station are in the same orbit, even within floating distance of each other, to immerse myself in the story. Thankfully, when it comes to sound design in Gravity, good storytelling and accurate science are not in contradiction with each other, and the result is Oscar-winning.

References & Further Reading

- ‘Gravity’, Warner Bros Pictures (2013).

Listing image: Warner Bros Pictures